L’espace comme terrain, quelques enseignements de l’anthropologie (2)

L’espace comme terrain, quelques enseignements de l’anthropologie (2). Entretien avec Valerie Olson

Mots-clés : anthropologie ; système ; environnement ; NASA

Valerie Olson est anthropologue et enseigne à l’université de California-Irvine (UCI). Elle se consacre à l’étude d’écosystèmes spatiaux, marins et désertiques, en faisant émerger la notion de système pour en expliquer la production scientifique, sociale, politique et culturelle. Cet entretien concerne avant tout la pensée originale qu’elle a développée à partir d’un travail de terrain mené au sein de la NASA depuis 2005. Ses réflexions paraîtront prochainement dans un ouvrage, American Extreme: an Ethnography of Space as Ecosystem (University of Minnesota Press), dont nous ne manquerons pas de publier un compte-rendu sur ce blog. Ségolène Guinard a effectué un séjour de recherche dans le cadre de sa thèse au département d’anthropologie de UCI à son invitation. Cet entretien revient sur les aspects les plus marquants de la recherche de Valerie Olson, avec lesquels notre contributrice a pu se familiariser pendant six mois. L’entretien a eu lieu à Irvine, Californie. Nous le publions en anglais, langue dans laquelle il a été tenu.

Humanités spatiales: What was your main question, as an anthropologist, when approaching for the first time outer space as a field of inquiry?

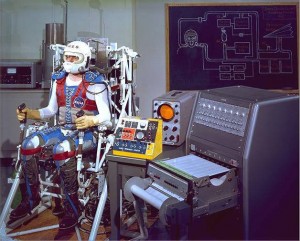

Valerie Olson (VO): My anthropological interest in outer space started with a graduate school course project. I wanted to know how people practice medicine in outer space where environmental conditions can’t be backgrounded or taken for granted – that is to say, where there is no standard or “normal” environment. Through this project I gained unusual access into NASA, and into the complex network of disciplines and sites that interact to make spaceflight possible. I was then driven to understand how people come to recognize terrestrial, and by extension human, nonseparation from outer space as an environment-at-large and what they do with that recognition.

Humanités spatiales: Were you already influenced by environmental anthropology?

VO: I trained in biomedical anthropology then switched to environmental anthropology, although I continue to combine these subdisciplines. I found that in biomedical anthropology, environment is often treated as a more stable variable than bodies and biological factors. Since I was intrigued by the overwhelming problem of keeping bodies alive in outer space, and space has been categorized as an environment since the early 20th Century, I turned to environmental anthropology to find ways of exploring the relationship between the production of biomedicalized bodies and biomedical environments. Now my research program focuses on the interdisciplinary production of explicitly ecosystemic spaces and relations.

Humanités spatiales: What is the specificity of your ethnographical approach of outer space?

VO: There has been some great work on space as a site for the production of political geographies and social imaginaries. You have featured several people in this blog who have been leaders in this, such as Alexander Geppert. They provide ground for my research. With some notable exceptions, much of that work focuses on technologies of rocketry and remote-sensing or on critical examinations of spatiality. My ethnographic interest in human spaceflight as a practice is on the conceptual and environmental technologies that make it possible to make outer space habitable, in a symbolic and actual sense.

Working on my project on space medicine made me aware of the modern proliferation of environmental kinds – from urban or extreme environments to ecological spaces and ecosystems. Unlike “Nature” which can invoke a kind of monolithic spatiality, even if we deploy Descola’s notion of multinatures, “environment” in the West is an already-pluralized concept because it’s always been socially differentiated in a Durkheimian sense. It is a mode for the specialized production of modern spatial difference, so now we have multiple and contingently overlapping environments and environmental conditions. I am interested in the sentinel modern paradox of the emergence of a concept of a “total environment,” as Rachel Carson defined it as a matter of concern in Silent Spring, and of multiple environments consolidating different imaginations of relations and problems. Modern social worlds can be multienvironmental.

Outer space is labeled an extreme environment, which animates it as a charismatic, solution-generating environment for imagined social futures. The idea that this infinite and highly diverse space, outer space, would be crammed into a category – along with other spaces like the undersea, prisons, deserts, and the poles – was fascinating to me.

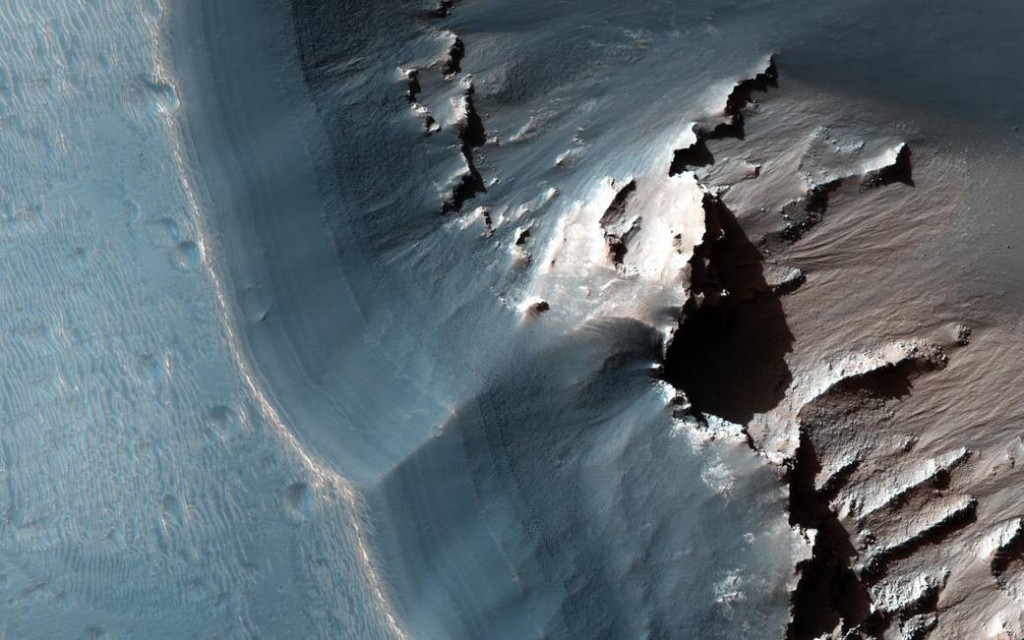

« Space is the most of what nature is. » Ici, sur Mars, la région Labyrinthe Noctis par la sonde Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (novembre 2015). © NASA.

Humanités spatiales: How has your hypothesis changed over the years?

VO: I went into this project looking for nature and technology, and I found environments and systems. That is because I listened to my data, which is where the theoretical material lies. Of course in the early process of project conceptualization, you have to impose theory on your field and on your object of study, but you have to know when to keep that theory and when to let it go. I imposed onto my project proposal some time-honored theorizations from anthropology and science and technology studies, all focused around the problem of contemporary nature and the nature-culture divide. So, I would ask my interlocutors questions like “Is space a part of nature?” and that would cause these incredibly shocked reactions, and some of them would reply that it was a nonsensical question. But I deliberately asked it because I wanted to provoke some response about Nature, about any sort of supposed divisions between earthly nature and cosmic nature. Which they then refused to make in terms of nature. And I began to pay attention and realized I was the only one using the term “nature”! My favorite response from an interlocutor was “space is the most of what nature is, but that does not help us get into space.”

Everyone spoke in terms of environments, and I began to listen very carefully to the presence of the word “system” alongside “environment” and also pay attention to how NASA was organized in terms of environments and systems. And, paradoxically, human spaceflight is the arm of U.S. aerospace most concerned with ecological problems and questions, but the least likely to use the term “nature.” As compared with other fields such as astrobiology where “nature” does come up. Most of the time, if we consider the operational terms used to launch spacecraft, put robots on planets, and put humans into space, the term being used is environment.

Humanités spatiales: I had a similar experience with the word “ecology”, that many of my interlocutors were reluctant to use, speaking rather about ecosystems…

VO: Right. “Ecology” has come to be used in non-science worlds as a synonym for environments or interdependent relationships in and of environments, but in most scientific and technical settings this is considered incorrect, which is worth paying attention to. Nevertheless it’s interesting how and why social scientists and humanities practitioners since Bateson have used the term differently and rendered it theoretical in particular ways, and sometimes I wonder if this is helping us theoretically or not, when it comes to how the term is actually being used in the world.

In the NASA dictionary of terms, you will see reference to ecosystems and ecological systems as things, but ecology is simply defined as the study of organism-environment relations. And NASA practitioners are among the inventors of iconic forms of “semi-closed ecological systems,” so despite the lack of ecologists and an operative sense of ecology in human spaceflight, they are indeed producers of ecologics and ecological things. And in the U.S., the ecological sciences, space sciences, and nuclear sciences grew up together and shared spatial fields and boundary objects. But to call a space or set of things “an ecology” is something that bothers the aerospace and terrestrial scientists that I’ve worked with.

Humanités spatiales: How has a concept of “system” emerged from the in-depth ethnography you conducted at NASA?

VO: Scientists and engineers there use “system” to designate purposefully self- or human-made organized sets of relations at scale – systems can define the boundaries of environments and also traverse environments.

This happened with the importation of general systems theory into the U.S. and the enthusiastic take up of system in many disciplines. I am making “system” an object of study because it is a highly politicized but also highly neutralized term. It is a term that organizes the designation and production of particular things and spaces in functionalist and relational terms, but is also used to organize the very forms of social production of those objects. People at NASA are assigned to systems, they work for systems, they speak for systems. They become, as some of my interlocutors have told me, “systems people”. This is a very interesting term that unites the material and sociopolitical dimensions of their practice.

In the West, even outside of NASA, it is very clear how systems are more than concepts. They have come to organize social worlds and spaces and even forms of mind activity. And yet this prevalent phenomenon is poorly understood ethnographically. This is in part because social scientists, particularly in the U.S., have rejected “systems theory” as idealistically totalizing and holistic and as a tool of colonial knowledge production, which it is. So, they have turned to terms like network, infrastructure, and assemblage to do the work of theorizing relations when in fact each of these terms has its own embedded history as technical, military, physics, and even systems theory derivatives. And ethnographers still use system in their work, as a descriptor. As a result, we don’t really attend to system as a certain kind of relational object with a particularly interesting conceptual history as, to borrow from Marilyn Strathern, a generic term like “relation” itself.

In my mind we don’t need more systems or post-systems theories, we need a theory of system. The question is: how do we theorize system as an object of social conceptualization and a tool of working practice? I offer a simple solution by saying it is a relational technology with three particular modes that I describe in my book, so that I can try to keep a connection between its conceptual and ethnographically specific working properties in the world. I am trying to think of “system” as a modality, to paraphrase Foucault, around which events and practices are organized, but also which creates events and practices. Some scholars such as Katherine Hayles, Cary Wolfe, and Fred Turner have turned their attention to understand system as a historical theoretical construct, but there is certainly more ethnographic work that can be done. Especially in the US, where “systems literacy” is now part of the national educational curriculum.

When you consider that the “system” term is used to build basic theory in physics and biology, and even in supposedly post-systems philosophy like Deleuzian theory, system is a technology of reality. By turning system into a cultural object of study, what I am hoping is it can be fit into a larger anthropological framework for studying forms of relationality as forms of difference. As Strathern has pointed out, much anthropology is based on following or concluding that everything is interrelated, not on trying to explore the conditions and modes of its own given theorizations of relationality. What does it mean that we theorize relationality from within functionally differentiated disciplines rooted in Western philosophy and social organization? This problem is, I think, not exactly the same as attending to epistemological or ontological difference, but to the very structures of separation, nonseparation, and relationality that make those basic philosophical categories seem different and only provisionally connected in certain social settings.

Humanités spatiales: One feels rather alone in the universe, especially when one is a student in social sciences or in humanities. What were the most inspirational works for your own research?

VO: I was initially inspired by the work of Debbora Battaglia who is a brilliant scholar who took a risk to take outer space seriously as an organizing framework for the group – the Raelians – that she was studying. She edited a book called E.T. Cultures which I read at the same time that I was doing my space biomedicine project in graduate school. It thrilled me that an anthropologist would create volume around the role that the category of the extraterrestrial plays in providing kinds of unearthly structure, in space and time, to imaginations of embodied and communal difference. So she, Peter Redfield, Stefan Helmreich, Diane Vaughan, and Stacia Zabusky were all figures who inspired me to get into outer space as an anthropological field.

Humanités spatiales: We keep talking about outer space in general, avoiding to add the word « culture(s) », because you told me once that the notion of field was already a way to embrace that which is beyond human. Could you try to explain this statement and describe what your field have been?

VO: I love the term “field” in anthropological work because of how it escapes certain kinds of political geographic borders. The term in English immediately brings to mind the plasticity and contingency of space and time, in which one can experience that there are fields of energy and fields of flowers, black holes and worm holes – which I imagine I could experience – that create force fields and infolded fields within which things transform in ways beyond human comprehension. And yet there are also fields of experimented agriculture within which people can be controlling but also immersed in the practice of watching things emerge on their own terms. I feel that fields are inherently emergent and interdependently rendered, and demand the synergistic engagement of our bodies, minds, and social experience through which some kind of understanding and meaning emerges that I can offer as an anthropologist. For me, to go into the field is as much a conceptual act as an embodied act. To be an anthropological fieldworker is always to be hyperaware of the in- and outfolding relations of the real actual and virtual dimensions of our practice.

The English language phrase “outer space” is fabulous because it is bounded and yet supposed to be infinite and encompassing. We can’t speak of it without marking an inner/outer divide. To have your field be outer space brings immediately to mind the paradoxical issue that people call outer space outer but they are also in it. We are all in this space people call outer space, on this planet, regardless of conceits that there is an inner space and an outer space or an inner environment and an outer environment. The marked phrase “outer space,” and the assumption that it isn’t a field one can be in, is very generative and productive for questioning the production of anthropological parts and wholes. How did people come up with this complex Latourian purification of cosmic space in order to make sense of where they are and where they are not? Outer space as an artifactual concept is tremendously interesting. “Outer space” gets invented in the 18th Century and becomes commonly used in the 19th. And let’s take a look at the expression “solar system”, which in fact John Locke may have coined. It has this incredible history as a geographic demarcation of the liberal subject and the liberal subject’s specifically relational and political space. That history emerges whenever one pronounces “outer space.” It’s a meaningful binary spatial division that impacts western social imaginaries and political action.

Humanités spatiales: Is your conception of field an analogy to the conception of environment that your research subjects might have expressed about outer space? How would they define the environment?

VO: They use a very technical and traditional definition of environment based on systems theory: environment is a set of conditions within which the system has to adjust, against which the system defines itself as a unified set of co-functioning things, and within which the system has to survive. It is therefore very specific in space. For instance, technically speaking, the astronaut is not in outer space. The astronaut is in a spacecraft, the environment of the spacecraft. And the environment of the spacecraft is changing outer space conditions plus changing interior vehicle conditions, and everything in it, including other people’s cells, dead plant leaves, spreading microbes, the radiations that streak through their bodies, and the condition of weightlessness. So environment is a spatial term that is dynamically and intricately additive and subtractive in space work, it’s always in the making.

Humanités spatiales: Do you have a different understanding of what an environment is?

VO: Environment is a sociocultural category, and I am interested in the conditions which concepts of environment depend on. I am also interested in the social production of ecosystems. People think of ecosystems as the most naturally given relational space in which we belong. They do not associate it with the work that goes into making it. The spacecraft is an ecosystem as well – it is the most highly produced and intricately provisioned ecosystem one might imagine. I therefore investigate the co-production of space and spacecraft as ecosystemic things. Both of them are products of labor, money, bureaucratic organization, the connectedness between the military and civilian spaceflight, all happening within the contemporary world of global economic and environmental totalizations. And now “ecosystem” is used to refer to cities and even financial payment systems. It is a term used to mobilize beyond-human sets of relations, in ways that escape the fact that it is an incredibly huge product. This is why I address ecosystems as built things even at their biggest scale, “system” being the technical term that allows that scaling to happen by black-boxing relations and separations along the way.

Humanités spatiales: Dealing with space as an environment, you seem to have resisted vitalistic approaches of matter and unfolded a reflection that gives space to configurations entangling the living with the non-living as such. Why have you become concerned with inanimate matter?

VO: The biocentric path of the human sciences is at a bit of a crossroads. What I love about systems as objects of study is that they encompass and transect living and non-living. You can speak of an atomic system, you can speak of a biological system, and immediately everybody knows that you’re speaking of something that hangs together because its organization produces a certain kind of function that keeps everything together. That is the cultural definition of system, that is, a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts, or that it is autopoeitic. In the fields that I’m engaged in, life itself is never foregrounded against the background of the environment, or against non-life. For instance food in space is considered biochemical, in two senses, the biological and physical: it impacts both body and the spacecraft. Food in aerospace is as much a part of the vehicle as it is a component of the human body. A poorly nourished body will kill the spacecraft, just as much as a poorly fueled craft will kill the body. The slippage between living and non-living, in the extravagant and relentless preponderance of the non-living that space represents, is hard to ignore. All the vitalism in the philosophical world is not going to change that. Nigel Clark explores this issue in his work on the inhuman.

A consciousness of the constructedness of vitalism, in a material and conceptual way is important, and I try to restore some understanding of that. This does not devalue life. It may decenter life, but in doing so it adds a dimension of specificity and urgency to the problem of life/nonlife that can be overlooked otherwise.

Humanités spatiales: I understand you are not dealing with the ascription of life to matter; yet, when reflecting upon an anthropological concept of environment in such « strange » places, has the question “is it alive or not?” emerged at some point? For instance when encountering the question of robots, that are viewed by some astronauts as collaborators?

VO: The notion that robotic machines are collaborators and partners is a very complicated thing in spaceflight. Janet Vertesi has done a wonderful work on technomorphism in space work, in which people who work on the Mars rovers learn to see like a rover and to work like a rover. This has the effect of creating not the anthropomorphism of the robot but the technomorphism in the human. In my field sites, I saw not the coding of robotic devices with life but a systemic intercoding between the robotic and the human in emergent ways, which are maybe limited by language and by the prejudices of the human as the master of the robot. Yet, in a day to day level, I think it is more intense in human spaceflight because people learn to love the spacecraft – it is the condition of their survival. They do not have to animate the spacecraft but they have other feelings that we associate with feelings that people have towards living things. But it does not mean that they make it alive. They are very aware that it is not alive. I have never encountered astronauts gendering the spacecraft or enlivening it in an anthropomorphic way. Yet there is a definite understanding of the contingency of the boundaries and connectedness that exists between the living and nonliving. People in space are minority objects. The fact that there are more machines than life where they live is not inconsequential.

When designing moon habitats, designers and engineers are interested in exploring how humans can contribute to the integrity of the habitat: human urine and waste is literally on the table as insulation and building material. The human body and the craft or habitat have exchangeable, tradable, features. Where does the body end and the spacecraft begin? Everything is a habitation resource, including what is in the body and bodies themselves. I like and I’m interested in how that does not equate with vitalism, but with a kind of sym-ontology or something. There are few English language words adequate to the task of describing this.

« The fact that there is a notion of the supernatural is not just a transcendental error, it retains some of the affective sacredness implied by the concept of nature. We should ask about the consequences of losing that. »

Le Douanier Rousseau, Le Rêve, 1910 (tableau conservé au MoMa).

Humanités spatiales: Where is “Nature”? [Nature have been a recurrent question for anthropologist, but are we really done with it, as Timothy Morton would wish? How do you situate yourself in the debate around the use of this word?]

VO: Nature haunts environments. In the West, nature has been a whole concept within which to fold existence, and against which to define the human. All our efforts to apparently dissolve nature, or merge it with other concepts, like natureculture etc. may not be attempts to dissolve it but to preserve it, because of what it does rhetorically and emotionally for humanistic perspectives. Environment and ecology are terms that threaten the distinctiveness and integrity of human beings. And I am glad of it. And then, as Tim Morton has argued, the idea of nature appears as a Romantic notion. But nature does preserve a spiritual sense, in the connected binary of natural and supernatural, as M.H. Abrams wrote about long ago. Is there such thing as the superecological? Nope. The fact that there is a notion of the supernatural is not just a transcendental error, it retains some of the affective sacredness implied by the concept of nature. We should ask about the consequences of losing that. And acknowledge that ecology as a concept does not really reoccupy that problem space, because everyone knows Gaia does not exist as a goddess, so that figure becomes, as my friend Lisa Messeri has noted, a kind of ironic ecological mascot. The problem of the sacred and spiritual are marginalized in anthropologies of technology and environment, and the funny thing is that there is a spiritual and metaphysical aspect to systems thinking cultures, as people like Hayles and Wolfe have noted and as Gregory Bateson’s work attests.

Humanités spatiales: What are the (other) pathways that you wish to explore in the future?

VO: I want to continue my project to explore contemporary technical modalities of connection and disconnection, and the ways in which new conceptualizations and practices of contingent non-separation are emerging in North American contexts. I can imagine studying the emerging politics of recycled water in Southern California, in which systems-based projects to merge or keep separate waste water and drinking water calls attention to ecological and affective politics that control the manufacture and distributions of recycled matter as “systems materials.”

Entretien realisé par Ségolène Guinard

1 À paraître aux éditions University of Minnesota Press. Le titre provisoire est American Extreme: an Ethnography of Space as Ecosystem.

2 D. Battaglia (ed.), E.T. Culture: Anthropology in Outerspaces, Durham: Duke University Press, 2006.

3 P. Redfield, Space in the Tropics, Oakland: University of California Press, 2000.

4 S. Helmreich, Sounding the Limits of Life: Essays in the Anthropology of Biology and Beyond, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015 ; ibid., “What Was Life ? Answers from Three Limit Biologies”, Critical Inquiry, 37, 2011, pp. 671–96.

5 D. Vaughan, The Challenger Launch Decision: Risky Technology, Culture, and Deviance at NASA, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997.

6 S. Zabusky, Launching Europe: An Ethnography of European Cooperation in Space Science, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995.

7 J. Vertesi, Seeing Like a Rover, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2014.

8 L. Messeri and V. Olson, “Beyond the Anthropocene: Un-Earthing an Epoch”, Environment and Society: Advances in Research, 6/1, 2015.